The Mysterious Elizabeth Pierce (Pearce, Peirce): a Parish Sexton

- History Revealed

- Jan 28, 2020

- 6 min read

Most textbooks dismiss women’s participation in the colonial society of Virginia because they seemed to exist solely in the shadow of their husbands. While many women were silent in the historic record, what about a woman who wasn’t married or who was widowed (femme sole)? She may be difficult to find, but she is a part of the historic record if you start to look at more than just legal documents.

We recently looked into the life of Elizabeth Pierce (also spelled Pearce and Peirce) in the John Glassford & Company store records. She had her own account (folio 122) in the 1760/1761 Colchester ledger, but also appeared under the Truro Parish collector’s account (folio 128), Robert Boggiss, Senior, as well as Boggiss’s personal account (folio 62). Pierce was only found in this one ledger from the Colchester and Alexandria Glassford store accounts. Her account showed she made a singular purchase on behalf of Robert Specks on a Thursday in early January 1761, and had a few items purchased on her behalf by Boggiss.

Pierce made this purchase on credit, nearly seven months before her account was paid off in August 1761. However, she was not the one to pay the account; the tithe collector for Truro Parish, Robert Boggiss, paid off her account. Why would Alexander Henderson, the store-keep in Colchester, provide a woman store credit to make her purchases? For Henderson to extend her credit meant Elizabeth Pierce must have been known in the community and someone to whom was deemed worthy of extending her over four pounds in credit. How did Henderson know Pierce? What was her relationship to Truro Parish and why would the tithe collector pay her account?

Fortunately, the vestry minutes for Truro Parish survive and provide some answers – and more questions – regarding Elizabeth Pierce and the tithe collector’s payment on her behalf at the Colchester store in 1761.[1]

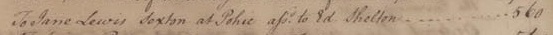

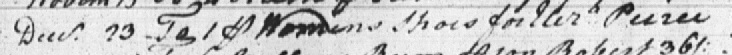

On 27 November 1758, six vestrymen for the Truro Parish met to discuss the business of the church, document the expenses of the previous year, and set the tithable rate to be collected to pay those expenses. As part of the church business, the vestrymen assigned a clerk for the vestry, sextons for the Upper and Pohick Churches, and church wardens for the upcoming year. It is the assignment of a sexton to Pohick Church where we first meet Elizabeth Pierce, newly appointed to the position. In looking back at previous sextons at Pohick Church, Richard Lewis served from 1753 until 1756/1757, when his wife, Jane Lewis, became the sexton. She was paid 560 pounds of tobacco in 1757 (the same amount as her husband in previous years). But, in 1758, at the same meeting Elizabeth Pierce became the sexton for Pohick Church, Lewis’s payment was made to Edward Shelton, indicating she most likely died, and why the church would be in search of a new sexton.

Vestry Minutes for the meeting on 27 November 1758 when Elizabeth Pierce was designated as the sexton at Pohick Church, replacing Jane Lewis. Images courtesy of Pohick Church.

What was the role of a sexton in the church? As with today's Episcopal church, a sexton’s responsibilities included care (cleaning) of the church buildings, the churchyard, and any property belonging to the church, including the “ornaments” for services. In colonial Virginia, the vestry appointed the sexton, and it was often someone who might otherwise have needed parish assistance (poor, widow, orphan, ill/handicapped). A sexton had been a paid position within the church since at least 1642/3:

"That every minister have his clark [clerk] and also sexton, for the keeping cleane of the churches, & other services in the absence of ministers according to the cannons of the church of England, & his or their meanes to be allowed by the parishioners."

Act I, March 1642/3, Hening’s Statues at Large (241)

On average, the salary for sextons was 500 pounds of tobacco. Because widowed women could find themselves at the mercy of the church, they would be tasked as a “sextonness” to provide them an occupation and a salary.[2] Possibly how both Jane Lewis and Elizabeth Pierce found themselves designated as the sexton of Pohick Church? The year after Pierce’s appointment (at the 12 November 1759 meeting of the vestry), her salary went to John Pierce rather than directly to her. However, in 1760, the vestry minutes specifically state the salary “to be paid to herself”. Why the change in status? Who was John Pierce and what became of him? Was he Elizabeth Pierce’s husband (most likely) or father or brother? In subsequent years, all payments were made to Elizabeth Pierce (and its various spellings, Pearce/Peirce) alone.

Pierce continued to be paid as the sexton of the Pohick Church until 1765, when the sexton changed to Elizabeth Davis. We suspect Pierce remarried and became Davis, as there was no notice of a change of sexton in the vestry minutes. Elizabeth Davis continued as the sexton until 1766, when she was paid for fourteen months of service, and with Charles Wright paid as the sexton in 1767. Davis (Pierce) likely died sometime in early 1767 and Wright took over her responsibilities.[3] From 1757, when Jane Lewis became sexton, until 1767, the last year Elizabeth Pierce/Davis received money, the salary of sexton remained unchanged at 560 pounds of tobacco – the same amount paid to all sextons for churches in Truro Parish.

In returning to the Colchester store ledger, Elizabeth Pierce decided to turn 540 of the 560 pounds of tobacco she was paid by the Truro Parish Collector (folio 128) to pay for purchases made on her account on behalf of Robert Specks (folio 122). As sexton, Alexander Henderson would know Pierce from Sunday services, and know she received an annual salary of 560 pounds for her care of Pohick church – and why he likely extended her credit in January 1761, knowing she would receive payment from Truro. What we have yet to determine was, what was the relationship between Pierce and Specks? Why would she turn her sexton salary, nearly in full, over to Specks to make purchases on her account? Given part of the debits included 25 shillings, Pierce must have owed Specks money either in her own right or on behalf of John Pierce.[4]

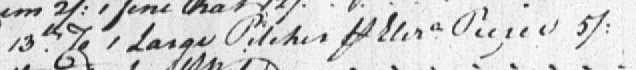

An even more tantalizing relationship needing to be determined was the one between Elizabeth Pierce and Robert Boggiss. Two weeks after the vestry approved her 1760 salary, Boggiss purchased a pair of shoes for Pierce; and in mid-June 1761, he bought her a large pitcher. Shoes might be explained as charity (helping the widow), but why would he buy a pitcher for her? For what purpose did she use the pitcher?

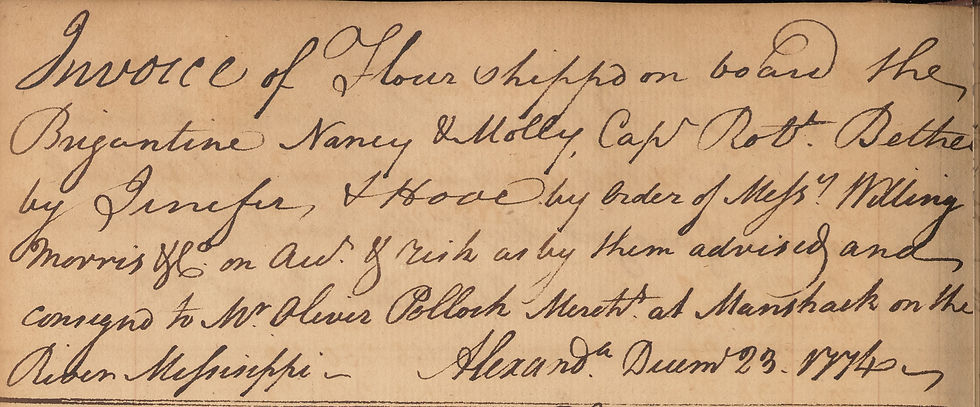

Robert Boggiss's purchases on behalf of Elizabeth Pierce: 23 December 1760, a pair of shoes, and 13 June 1761, a large pitcher (folio 62).

While 21 women appeared in the Colchester 1760/1761 ledger with their own accounts, including Elizabeth Pierce, at least an additional 45 women can be found within accounts of other people. When we take a moment to look more closely at when and where the women appeared, we begin to learn more about their lives and the role of women in Virginia’s colonial society.

Please let us know if you have any additional information about Elizabeth Pierce, or the other players in her life, as we explore the lives of the women found in the store accounts.

Notes

[1] Church of England (1995) Minutes of the Vestry: Truro Parish, Virginia, 1732-1785. Baltimore, MD: Gateway Press, Inc.

[2] Seiler, William H. (1956) ““The Anglican Parish Vestry in Colonial Virginia.” The Journal of Southern History, Vol 22 (3): 330; Hallman, Clive Raymond (1987) The vestry as a unit of local government in colonial Virginia. University of George: Doctor of Philosophy, Dissertation: pp 52, 135, 227.

[3] Wright remained the sexton at Pohick Church through at least 1776, when payments to sextons were no longer noted/reported in the church’s expenses for the previous year.

[4] Robert Specks also had his own account in the 1760/1761 ledger where in February and April (1761) he bought a hat, shoes, a bottle of snuff, osnaburg, and brandy (folio 125). We believe his surname later becomes spelled as “Speake” and he appears in the ledgers through 1769 (however, he falls on hard times in 1766/1767 appearing in the Desperate Debts accounts). Beth Mitchell’s Fairfax County, Virginia in 1760: An Interpretive Historical Map (1987) identified a Robert Speake as a tithable in Fairfax County, but was unable to place him on the map.

Comments